Know-it-alls tend to overestimate their knowledge and cognitive abilities – and are probably more unpleasant contemporaries

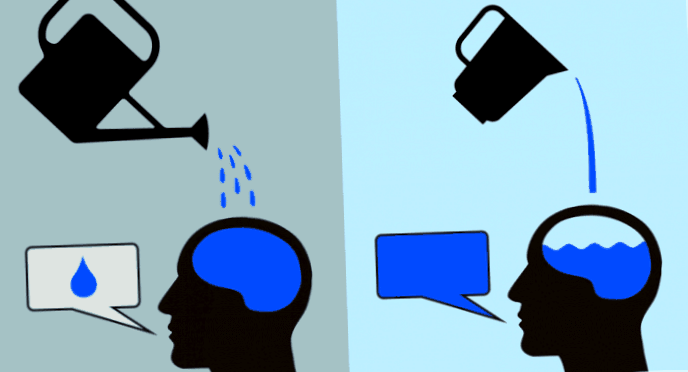

It sometimes seems that those who know the least are convinced that they are well informed. Scientists had recently published a study according to which Facebook users who are content to read only the previews of linked articles in the newsfeed are happy to overestimate the knowledge they have gained as a result. They are driven by feelings and are looking for them, a quick glance is enough to be convinced of their alleged insight into facts, without having to look further for real correctness or read the whole article. There is a lack of awareness of the limitations of their knowledge.

This can also be expressed the other way around and follows the traces of Socrates, whose motto is said to have been: "I know that I know nothing." Which is not to keep the blinders on calmly, but to try to get to the bottom of things with your own thinking and questioning. To put it a bit more simply, it seems that people who can admit to themselves and to others that their knowledge and beliefs cannot be correct, that they are questionable, actually know more and are smarter than the truth tellers who are convinced of the correctness of their opinions and knowledge.

Psychologists led by Elizabeth Krumrei-Mancuso of Pepperdine University speak in their article in the Journal of Positive Psychology of a "intellectual humility" People who are capable of self-criticism because they accept that they can be wrong. Ultimately, this also means that they are curious and willing to experience or learn new things. Those who barricade themselves intellectually do not want to know anything more and reject new things because they trust their own views too much.

To explore the implications "intellectual humility" The psychologists conducted five surveys with a total of 1,200 test subjects to determine the effect of the. For example, subjects were asked to rate their problem-solving abilities in comparison with other people and then given a corresponding test of their cognitive abilities. It turned out that "not-all-knowers" underestimate their cognitive abilities, while those who do not underestimate their problem-solving abilities underestimate their cognitive abilities "Know-it-all" they overestimate. More men are omniscient than women.

However, the situation is not quite simple. In another test with students, the know-it-alls, who were asked about their self-assessment at the beginning of their studies, scored slightly better than the self-doubters. People who learn easily or know that they will get good grades are obviously more confident about themselves. However, another test that examined general knowledge showed that "intellectual humility" is associated with better general knowledge as well as with higher cognitive reflexivity and lower self-assessment.

Overall, the researchers found that "intellectual humility" with a better self-assessment of one’s own knowledge, even if one’s own abilities are sometimes underestimated. In addition, correlations were found with reflective thinking, intellectual motivation, curiosity, intellectual openness, and open-mindedness. Intrinsic willingness to learn is higher, while the tendency to punish others (vigilantism) is lower.

However, there is no connection with better cognitive skills. So you can be intellectually closed and overestimate yourself, but be just as smart as the humble ones. So it could be, what the scientists suspect, that "intellectual humility" is related to learned skills and knowledge performance (crystalline intelligence), but not to problem-solving ability (fluid intelligence). Intellectually humble people – an extreme counterexample would be Donald Trump – are not smarter, but probably just more self-reflective and more sociable, probably the more sympathetic people who also want to know what others think.